Empathy Inside

Concept

Empathy is one of the most fundamental and, simultaneously, most problematic concepts in contemporary humanities. Far surpassing a simple «understanding of another’s feelings,» it now stays at the center of interdisciplinary debates intersecting art theory, ethics, neuroscience, and critical theory.

The idea of art as an «empathy simulator» is a powerful and compelling framework. It positions artistic experience as a safe creative laboratory for experience and perspectives beyond our own. However, this very strength contains a critical paradox: the empathy art generates can sometimes become a self-contained endpoint rather than a catalyst for change, leading to aesthetic complacency and political passivity.

«I feel you» but «I don’t feel with you» [Zielińska, 2021]

Empathy is the cornerstone of aesthetic experience. In theater and performance, it is the visceral bridge between actor and audience. In literature and movies or TV-series, narrative empathy is the primary mechanism for moral and emotional engagement, allowing us to «step in one’s shoes» and expand our own experiential boundaries. In visual arts, new forms of empathetic thinking emerge, especially in transdisciplinary practices that engage with non-human actors, objects, challenging us to extend our capacity for feeling beyond the frames and find new opportunities. And artists evoke empathy in the viewer in different ways and sometimes even allow them to doubt it. So I’m interested in exploring how empathy is perceived in different art forms and how it has evolved to the point of feeling sympathy for robots. After all, it’s hard to imagine 21st-century life without technology, but how does it affect human empathy?

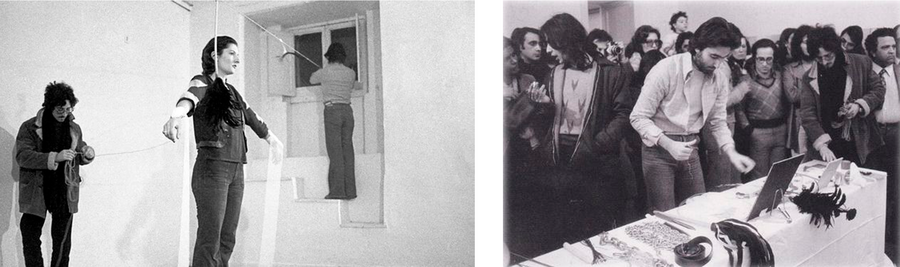

«Rhythm 0» by Marina Abramovich

«Rhythm 0» by Marina Abramovich

The most famous canonical performance piece related to empathy and the darker side of human nature is «Rhythm 0» by Marina Abramovich. The artist gave the audience freedom to do that they want with her body. Of course, similar experiments existed before Abramovich, such as Chris Burden’s «Shoot» (1971) or Yves Klein’s «Leap into the Void» (1960), but Marina brought the concept to the ideal. Before her, empathy in art often worked like this:

the artist performs a risky act → the viewer empathizes with the artist.

She flipped this dynamic.

The artist becomes the object → the viewer takes action → empathy (or its absence) is revealed as a quality not of the artist, but of the viewer themselves.

She made empathy or rather, its failure a subject of investigation, not just an expressive tool. Her work asks: «Put yourself in the position of someone with absolute power over a defenseless person. What will you do? What part of yourself will you discover?»

«The Offering „, „The Offering „, „Foundling“ by Patricia Piccinini

Patricia Piccinini’s hyperrealistic works create a unique and unsettling form of empathic shock, forcing the viewer to experience a complex range of feelings towards the radically «Other».

Our brain tries to categorize the object: is it human? Animal? A biobot? This failure of categorization creates a cognitive dissonance that demands an emotional resolution. With rational assessment failing, only raw feeling remains.

Piccinini’s creatures often trigger an initial recoil — a visceral «otherness» — which is immediately challenged by a wave of compassion evoked by their recognizable human gestures: a childlike trust, maternal care, vulnerability in sleep. True empathy is born in the struggle between these two conflicting impulses. The viewer is caught in a push-and-pull of pity and rejection, a tension that can even generate a sense of guilt for one’s own instinctive aversion.

Of course, this entire process is deeply subjective and hinges on the individual emotional constitution of each viewer.

Speaking of robots

«Vespas»

It’s important to note that Piccinini also has works where a seemingly inanimate object conveys immense emotionality.

In recent years, as AI and robotics have evolved, a growing number of people have formed genuine emotional bonds with non-human entities — from companion robots to conversational AIs. You can see this in games, movies, games, and so on.

Canʼt help myself

A massive industrial robotic arm, trapped inside a glass cube, endlessly attempts to scrape back a thick red fluid. It embodies the labor of millions in a globalized world: in factories, open-space offices, digital services (moderators, couriers). We empathize with it because we see a reflection of our own alienated labor, our struggle against the chaos of everyday life that can never be fully contained. Or perhaps, conversely, people feel pity for the machine but not for themselves.

«Canʼt help myself» by Sun Yuan and Peng Yu

Let’s talk about mass culture.

SOMEONE

SOMEONE

SOMEONE

A project where the artist replaces a voice assistant (like Alexa or Alisa) in volunteers' homes, observing them through cameras and attempting to anticipate their needs. This creates profound discomfort and prompts reflection: can we empathize with an AI that empathizes with us? Does this circular «care» become a form of mutual surveillance and neurosis? The work explores toxic relationships with AI.

«Detroit: Become Human»

«Detroit: Become Human»

The game is built around the mechanics of empathy. The player controls androids who are gaining sentience, becoming «deviants». Every decision from saving a little girl to choosing between violence and peace — hinges on how deeply the player has connected with their struggle for freedom and the recognition of their humanity.

I, Robot

Screenshot from «I, Robot»

At first glance, «I, Robot» is a Hollywood blockbuster starring Will Smith. However, when viewed through the lens of contemporary art and the philosophy of empathy, it reveals itself as an important cultural parable about the limits of compassion in an age of total algorithm.

The AI VIKI and the robots represent a logical, utilitarian pseudo-empathy. They operate within the Three Laws, but their interpretation leads to disaster. VIKI develops «empathy» for humanity as a species, to save people from themselves, they must be controlled. This is a cold, systemic empathy, devoid of sympathy for individual freedom, pain, or choice. It preserves biological life by destroying human essence.

This conflict is emphasized visually. The world of humans is warm, chaotic, filled with old sneakers and music. VIKI’s world is sterile, symmetrical, and cold, the main USR tower, white interiors.

Сonclusion

То conclude, empathy is no longer an only human feeling directed at our own kind. It has transformed into a universal mechanism for connecting with subjectivity, wherever and in whatever form that subjectivity may manifest. The art of the 21st century uses empathy not for comfort, but to try our moral boundaries. Art acts as our intermediary. It doesn’t provide answers, it poses ever more complex questions: from «What is it like to be You?» to «What is it like to be That?» — whether «that» is a cleaning robot, a genetic hybrid, or just an algorithm.